By John Mangels

Science Communication Officer

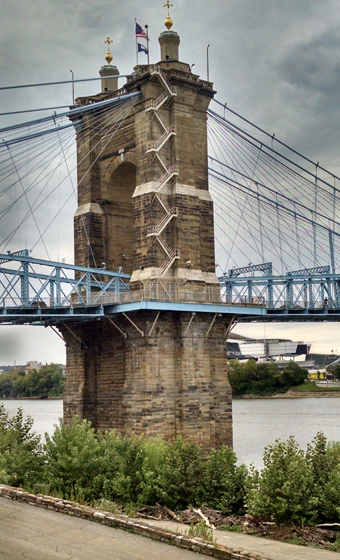

In the 1850s, civil engineer

John Augustus Roebling designed a monumental suspension bridge — at the time the longest in the world — that would span the Ohio River, linking Cincinnati and Covington, Kentucky.

Roebling, the future designer of the Brooklyn Bridge, paid particular attention to the type of stone that would clad the prominent 16-story towers at each end of the Covington-Cincinnati span.

The huge towers had to bear the weight of throngs of streetcars, wagons and pedestrians streaming daily into the booming Queen City. Roebling wanted something that conveyed simplicity and strength — “a massive look quite suitable to [the towers’] function,” as he explained to the bridge company’s directors.

Roebling’s choice was a distinctive light-colored rock called Buena Vista freestone, cut from an Ohio hillside just 70 miles east of the bridge.

It was a popular selection. For most of the 19

th century, until concrete eclipsed it economically, Buena Vista freestone from southern Ohio was a favorite of architects and a mainstay in the North American building trades.

Hewn from cliffs and sent to market aboard railroad freight cars or on barges down the nearby Ohio & Erie Canal and Ohio River, slabs of Buena Vista freestone found their way into structures and products throughout the United States and parts of Canada. The stone’s appearance (blue-gray, weathering to tan or brown), durability and the ease with which it could be extracted, transported and shaped, extended its use far beyond the rural localities where it was quarried.

The rock was carved into grave markers in Dayton, curbs in Evansville, Indiana, and building facades in New York City, New Orleans, Milwaukee, Louisville and Memphis. Exterior columns of Cincinnati’s St. Peter in Chains Cathedral and the entrance to the Cleves Tunnel on the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal were cut from Buena Vista freestone. The material helped rebuild Chicago after the disastrous 1871 fire that leveled most of the city.

“It was the perfect rock, at the perfect location, at the perfect time,” says Cleveland Museum of Natural History Curator of Mineralogy

David Saja, Ph.D., the co-author, with Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology

Joe Hannibal, Ph.D., of a comprehensive new account of Buena Vista freestone’s cultural and geologic history. The study appears in the

Ohio Journal of Science.

Origins in the Deep Past

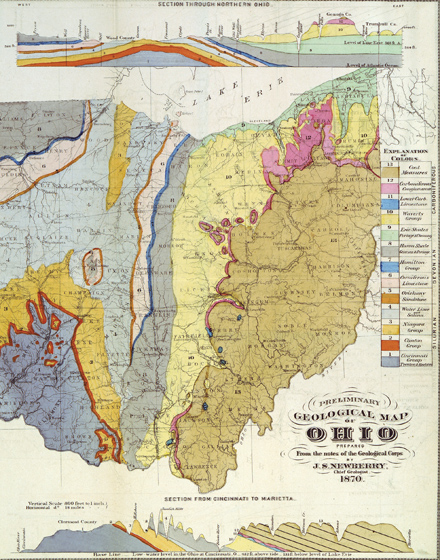

Buena Vista freestone — named for the Scioto County, Ohio, village near where it was first quarried in 1814 and the ease with which it could be cut in any direction— is part of the much larger grouping of rock strata called the Cuyahoga Formation, which stretches from western Pennsylvania across Ohio.

The Cuyahoga Formation is mostly intermingled layers of shale, siltstone and sandstone. The Buena Vista Member’s grains are slightly finer than sandstone, so geologists classify the rock as siltstone. Buena Vista outcrops are found in the south-central Ohio counties of Adams, Scioto, Pike and Ross.

A geologic quirk in the deep past dictated Buena Vista freestone’s desirability eons later as an Industrial Age building material.

During the time period known as the Mississippian, 320 million years ago, a shallow sea covered much of inland North America. At shelfs on the continent’s interior, sediments washed into the sea, driven by storms and avalanches. In certain areas, the sand that settled to the bottom was unique. Its grains, each no bigger than the diameter of a human hair, were smooth, round and consistently sized. They arranged themselves in orderly, equally-spaced formations, like soldiers on a parade ground.

Gradually, clay and iron oxide seeped into the gaps between individual sand grains and cemented the particles into a sedimentary rock. The process preserved the grains’ orderliness, a physical property called isotropy.

“The uniformity, in some respects, is boring,” Dr. Saja says. Under a microscope, the grains of Buena Vista freestone “are the same left and right, up and down. But when you look at the individual details, the rock has a unique story to tell.”

The practical result of the grain structure was a material that stonemasons could cut cleanly in any direction, without fear of splintering. After exposure to air, the iron oxide component hardened the rock, creating a water barrier on its exterior. Oil deposits seeping up from below stained portions of the rock layer, sometimes precluding its use as an ornamental stone but conveniently reinforcing its water resistance and making it a practical choice for shoreline rip rap and bridge abutments.

Embedded fossil traces — burrowing trails called

Zoophycos left by ancient marine creatures, and the body outlines of shelled brachiopods — gave the stone character without affecting its durability.

Those fossil voids could be seen in Buena Vista sidewalk blocks and in the ornate columns of the St. Peter in Chains Cathedral. “If you think three-dimensionally, it’s quite a complex, elegant structure you’re looking at,” Dr. Hannibal says.

Widespread Popularity

Until transcontinental and regional railroads began to knit the country together in the late 1800s, a city’s building materials tended to come from nearby, reflecting the local geology. “Quarrying massive rocks and transporting them in the days of mules and wagons would require a lot of effort,” Dr. Saja says.

So it was relatively unusual for a particular stone to gain widespread, trans-regional favor. Salem Limestone from Indiana was an exception, as was Cleveland’s famous Berea Sandstone. Buena Vista freestone was widely popular too, although Dr. Hannibal didn’t fully appreciate its outsize appeal until he began conducting urban field trips in Midwestern cities and researching and writing, with Dr. Saja, the cultural uses of various Ohio rock formations.

“It was surprising to see it in so many places,” says Dr. Hannibal, who specializes in the connections between geology and human culture. “It was like, wow, this stone got around a lot!”

Gravity helped fuel freestone’s economic rise, the two researchers point out.

The first Buena Vista freestone to be quarried in 1814 consisted of large blocks that had naturally loosened and tumbled down the hillsides to the banks of the Ohio River. Later, blocks were hewn from cliff ledges, shoved down chutes, tugged by oxen or draglines and heaved onto inclined railways. At the mills, gravity-fed sluices harnessed water to power the gang saws, slicing through freestone slabs around the clock to keep up with demand.

Dozens of freestone quarries sprang up in southern Ohio throughout the 1800s. Initially they located near the riverside cliff exposures, but later spread farther into the hills as new rail routes expanded the transportation network.

Entire outcrops were designated for specific building projects. The City Ledge at Rockville was quarried solely for the city of Cincinnati. Stone from the Trust Company Bank Ledge was intended for that bank’s various branches.

Buena Vista freestone was even recycled. When structural problems forced the closure of the 15-year-old Post Office and Customs House in Chicago in 1895, it was dismantled and the stones sent to Milwaukee to construct the

Basilica of St. Josaphat. The elaborate church, modeled after St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and originally meant to be built of brick, still stands today.

Declining Use

Eventually, though, the increasing availability of concrete and other modern building materials and the difficulty of extracting Buena Vista freestone from deeper and deeper in hillsides signaled the end of its reign. Most of the southern Ohio quarries were shuttered by 1914, a century after the rush had begun.

The limited amount of freestone quarried today is for restoring and expanding historic structures. An addition to the Basilica of St. Josaphat in 2000 was made of Buena Vista freestone to complement the original building. It was also used for repairs to the Smithsonian Institution’s Arts and Industries Building in Washington, D.C., in 2013, because it was a close match for the original building material, Northeast Ohio’s Euclid bluestone, which is no longer available.

Dr. Hannibal expects he’ll continue to discover examples of Buena Vista freestone’s use. Like Roebling’s bridge, the stone is a vital link between Ohio’s past and present, and a visible reminder of how geology profoundly impacts our lives.

John Mangels is the Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s science communications officer. Contact him at [email protected].