Thursday, December 15, 2016

Blog by John Mangels

Science Communications Officer

On Tuesday, Italian and Tanzanian scientists announced the

discovery of 13 fossilized footprints likely left by members of the same upright-walking human ancestral species to which the iconic

Lucy belongs.

The ghostly 3.66 million-year-old tracks were made by two individuals trudging through wet volcanic ash covering a bushland plateau in what is now northern Tanzania, Africa.

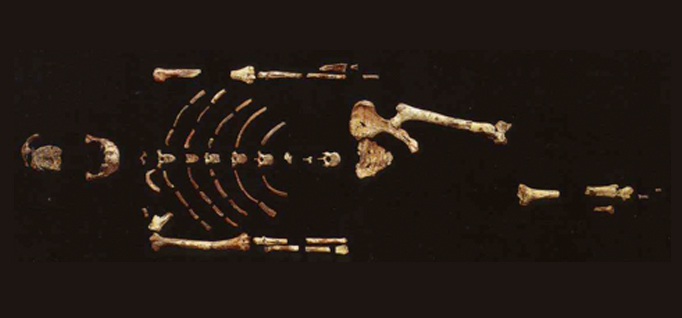

Fossilized 3.66 million-year-old footprints from Laetoli, Tanzania, left by two upright-walking early human ancestors. Photograph by Raffaello Pellizzon.

Fossilized 3.66 million-year-old footprints from Laetoli, Tanzania, left by two upright-walking early human ancestors. Photograph by Raffaello Pellizzon.

There’s no doubt this is an amazing find, deserving of the international attention it’s gotten. But there’s been some fairly uncritical reporting about the pronouncements the discovery team has made, based on the footprints, regarding the social behavior of Lucy’s species,

Australopithecus afarensis. The scientists have used the footprints as the catalyst to reinterpret a famous set of 3.66 million-year-old hominin tracks found nearby in 1976, suggesting the two pathways collectively represent a big, dominant male leading around a group of smaller females and juveniles — his “harem,” as one writer observed.

But two Cleveland Museum of Natural History experts caution that the new footprint evidence alone can’t support broad conclusions about

A. afarensis’ social structure, or even the gender of the hominins who left the tracks.

“My 13-year-old nephew’s feet are bigger than mine, so if we left footprints together, his could be interpreted as a large female’s,” says Curator of Paleobotany and Paleoecology

Denise Su, PhD, who specializes in the reconstruction of environments in which

A. afarensis and other human ancestors lived, and who does field research in Laetoli, where the footprints were found.

“A lot of the things they highlight as significant are not actually new to the science,” says Curator of Physical Anthropology

Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD, who has discovered and characterized some of the most important early human fossils ever recovered. “The inferences about social structure, to me, are a bit of a stretch. What they have is nothing more than a hypothesis, but they’ve written it as a conclusion.”

Let’s review some history and context, to better understand these concerns.

Upright walking, or bipedalism, is the signature trait of the evolutionary lineage of primates that led to modern humans. Although some recently recovered fossils hint that hominins may have walked on two legs as far back as 6 or 7 million years ago, the first clear evidence of bipedalism was

Lucy, the 3.2 million-year-old female

A. afarensis partial skeleton discovered in the Afar desert of Ethiopia in 1974 by an international team of scientists led by former Museum curator Donald Johanson, PhD.

Lucy (named for the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” which Dr. Johanson and colleagues played while celebrating the find), was small-statured, at slightly more than 3 feet tall, and small-brained, but had knees and other anatomical features adapted for walking. At a nearby locality, Dr. Johanson found a jumble of fossilized bones representing as many as 13 individuals — a group he dubbed the First Family and that were also members of Lucy’s

A. afarensis tribe.

More evidence for early bipedalism came with the 1976 discovery in Laetoli, Tanzania, by British paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey and colleagues of a fossilized trail of about 70 footprints left by two or three hominins walking in the same direction. The

Laetoli footprints were in a sediment layer 3.6 million years old, 400,000 years older than Lucy and the First Family. But it contained other

A. afarensis fossils, so the footprints likely represented the same species and reinforced

afarensis as a walker.

The new fossil footprints reported this week were found less than a tenth of a mile from the original Laetoli tracks, in the same volcanic layer. Whoever made them were trekking in the same direction — northwest — as the walkers from the first site. The scientists reported that casts of the footprints from the new site, called S, looked similar to photographs of footprints from the 1976 site, called G. Each set had deep, oval heel impressions and evidence that both collections of walkers gripped and pushed off of the wet ash with their toes at the end of their stride.

Using measurements of the length and width of the footprints, the angle of gait and the length of the strides, the Italian and Tanzanian researchers estimated the height and weight of the two walkers at the new S site, and the three walkers at the nearby old G site. (The foot length-to-stature ratio isn’t firmly established for

A. afarensis, which makes the height calculations tentative. Also, estimating weight from footprints can be imprecise.)

The researchers determined that the S1 and S2 individuals were a maximum of 5 feet 6 inches and 4 feet 10 inches tall, respectively, and weighed 106 and 92 pounds. Both were supposedly taller and heavier than the G site walkers, who ranged from 3 feet 9 inches to 4 feet 9 inches tall and weighed 73 to 90 pounds.

Here’s where the discoverers’ presumptions begin. They propose that the biggest individual at the new site, S1, is a male, and that because the others at the old and new sites are considerably smaller, they probably are females and/or juveniles. They assume that the S and G hominins were walking “in the same time frame” — in other words, that they interacted as a group.

And, most significantly, the researchers propose that the substantial size difference between the large, allegedly male S1 hominin and the other supposed adult females in the group — a gap they claim is even greater than the size variations among the First Family — constitutes a wide, gender-based size disparity, which scientists call extreme sexual dimorphism.

The degree of sexual dimorphism within a species is a product of evolution, and indicates the conditions in which males and females coexist. Modern men and women aren’t much different in size; from a stature standpoint, we’re mildly sexually dimorphic. We’re also basically monogamous. Males don’t have to use their physical size to compete with each other for female mates. Gorillas, on the other hand, have strong sexual dimorphism. Males are considerably bigger than females because gorillas are polygamous and males fight each other to mate and reproduce.

In the past, there’s been lots of debate about how dimorphic Lucy’s species was. Several members of the First Family were a good deal larger than Lucy, driving the perception that

A. afarensis was distinctly dimorphic. But in 2010 the Museum’s Dr. Haile-Selassie announced the

discovery of a long-legged partial

A. afarensis skeleton almost 5 and a half feet tall. He named it

Kadanuumuu, which means “big man” in the language of the Afar tribesmen of Ethiopia who helped unearth the bones.

Taking the taller

Kadanuumuu into account, a 2015 statistical analysis of

A. afarensis specimens led researchers from Pennsylvania State and Kent State universities to

conclude that Lucy’s species was only moderately sexually dimorphic.

“I think that’s reasonable,” says Dr. Haile-Selassie. Both he and Dr. Su question the ladder of assumptions the new footsteps’ discoverers had to climb in order to propose gorilla-like social structure and mating behavior among Lucy’s kind.

“Fossil footprints are so tantalizing,” Dr. Su says. “You see these footprints and you have a connection to them. It’s something we see that we leave behind when we walk on a beach. You want to be able to take it to the next level and understand them as social animals, but I don’t know how you can make that (sexual dimorphism and social behavior) connection.” Without a continuous footprint path between the old and new sites, “it’s impossible to prove that this was a social group that was traveling together and that this says something about their relationships.”

The new footprints’ value is their ability to highlight the need for additional research at Laetoli and the urgency of protecting and conserving the site. They were unearthed while the location was being evaluated for a possible museum, but the project has been slow-moving and the original Laetoli footprints are covered with a layer of rocks, raising concerns about their condition.

“This is a wakeup call for the Tanzanian government that they should do something,” Dr. Haile-Selassie says.

Science writer John Mangels is The Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s science communications officer. Contact him at [email protected].

Go back to all blogs