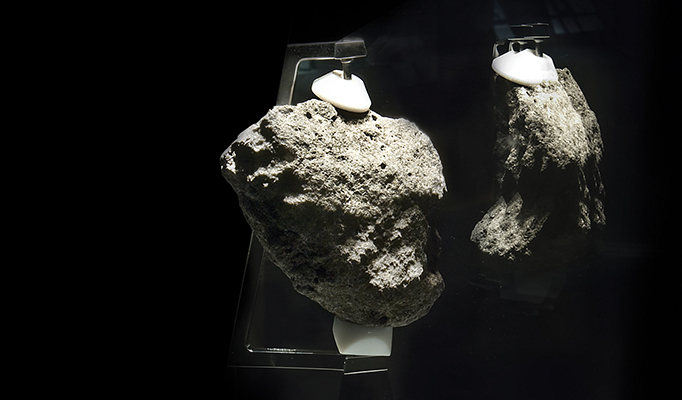

Inside the Cleveland Museum of Natural History sits an unassuming rock specimen. It is delicately displayed in a small glass case, and is about the size of a child’s fist. The rock weighs 253 grams—roughly the weight of two sticks of butter. It’s the most precious specimen on display in the Wade Gallery of Gems & Jewels. In fact, it’s so incredibly special, it’s been deemed “priceless and irreplaceable”—it has no estimable value that can be printed on a price tag.

This rock is not a diamond or a ruby. Nor is it a sapphire or an emerald. It’s certainly not something you’d ever find incorporated into a piece of jewelry. It’s not even shiny! So, what is this mystery rock?

It’s a piece of lava flow from the Moon’s surface, dated at approximately 3.2 billion years old. This small sample, labeled No. 12055, was collected 50 years ago from the Moon’s Ocean of Storms lava plain. It was originally buried under the surface, far too deep for anyone to ever find. Lucky for us, it was excavated from its resting place by a meteor impact. Once unearthed, the fragmented rock lay on the surface of the Moon for 15 million years until astronaut Alan Bean retrieved it during the historic Apollo 12 mission.

The mission successfully reached the Moon, second only to the famous Apollo 11. But this mission was historic in its own right. Whereas Apollo 11’s goal was simple—put man on the Moon—Apollo 12 was the first mission assigned the express purpose of collecting samples of the Moon’s surface.

After Apollo 11’s giant leap for mankind four months prior, NASA was eager to repeat its success, and it would spare no cost. Using today’s dollar value, the cost of Apollo 12, with the sole intent of retrieving geologic samples, would total about $10 billion.

Pete Conrad and Alan Bean conducting one of their two moonwalk expeditions as they collect Moon rocks, including Specimen No. 12055, which now calls the Museum home

Specimen No. 12055 on the surface of the Moon

TROUBLE STRIKES—TWICE

On November 14, 1969, the astronauts were departing from Kennedy Space Center, traveling at over 15,000 feet per second. Suddenly, in the midst of a storm, their spacecraft—a Saturn V rocket—was struck by lightning mere seconds after takeoff. But lightning never strikes the same place twice, right?

Wrong. Seventeen seconds after the first strike, the launch vehicle was hit again. Its electronics went haywire, and the astronauts, unsure of what had happened, were baffled. They worried they would have to abort the mission before even reaching orbit. Tensions began to rise.

NASA’s ground control urged the astronauts to reset the systems. But Alan Bean, the flight’s systems engineer and lunar module pilot, was hesitant. With the cause of the incident unknown, this could be risky. He noticed they still had battery power—a good sign. So, he took a breath, collected his thoughts, and finally flipped the switch that successfully reset the electronics.

Thanks to Bean’s calm, cool, and collected thinking, the mission was back in business. After overcoming a few other minor challenges, the astronauts were ready to make their landing.

CLEVELAND NAILS THE LANDING

It is said that the success of putting man on the Moon was not just a victory for America, but for the entire planet. Humanity had never achieved something so monumental up to that point, and many would argue we haven’t risen to that level of greatness since. And one Cleveland company, in particular, can claim a piece of the victory.

The lunar module descent engine (LMDE) used in the Apollo program was the first throttleable rocket engine. This feature enabled astronauts to make the delicate maneuvers vital for successful landing. And it was built by none other than Cleveland-based TRW Corporation.

Operating from 1901 to 2002, this aerospace company was responsible for solving one of the biggest challenges NASA engineers faced when building the Apollo 12 rocket. To ensure a soft, safe landing for the astronauts, NASA required that the LMDE have certain characteristics. NASA set three main criteria for the engineers: It must have high throttle, low weight, and, in the event of landing on top of a large rock, the ability to be crushed without destroying the rest of the spacecraft.

NASA, feeling uneasy about these hefty requirements, put TRW Corporation in competition with another company to produce the best design for the LMDE. TRW’s revolutionary design not only met its specifications, but it also beat out some tough opposition. The company had no way of knowing at the time what a bumpy start the mission would have, but its contributions made the near-disastrous operation well worth the risk.

After Apollo 11’s tricky landing months prior (which put it nowhere near target), Bean and the rest of the Apollo 12 crew were charting new territory. With the help of the state-of-the-art LMDE, the crew landed so precisely that they were able to visit the landing site of Surveyor 3 (a space probe that had beaten the Apollo missions to the Moon, landing on April 20, 1967).

This landing, aided by Bean’s expertise, was an incredible feat of navigation. Perhaps that’s why Bean tossed his silver astronaut pin into a crater before departing for home—he knew he’d be receiving a new gold pin upon his return.

COLLECTING SPECIMEN NO. 12055

In total, the flight crew, under the direction of commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, spent 31 hours on the Moon, completing two moonwalking expeditions while they were there. Together, they collected 69 samples, amounting to 34 kilograms (roughly 80 pounds) of Moon rocks, to bring back home.

But in the vast expanse of the Ocean of Storms, specimen No. 12055 was not just randomly chosen. The crew had undergone extensive training, meant to help them identify specimens that would represent the area’s overall geologic composition. In audio footage from November 20, 1969, you can hear the crew deliberating about whether to take a closer look at No. 12055. They were at the rim of Head Crater.

“Hey, you kicked over a rock that had a white bottom—quite a bit different than the top,” Bean said to his commander. “Pete, maybe you want it.”

Sure enough, the surface of No. 12055 was pockmarked with small, dark spots, called zap pits, which were caused by tiny meteor particles that bombarded the Moon millions of years ago. Bean’s keen eye is the reason you can see No. 12055 on display at the Museum today.

MAKING THE MUSEUM HOME

The crew received a hero’s welcome upon their return, and NASA got to work examining the samples they’d brought with them. It identified No. 12055 as a common basalt rock, with what you might call an uncommon origin (not every basalt rock is from the Moon, after all).

So, how did the Museum come to acquire this rare Moon specimen with such a storied history? Thanks to the dedication of passionate Museum staff and local professionals willing to help the cause, NASA agreed to give us one Moon rock on long-term loan.

“We solicited the support of the broad community of astronomy-related [experts] from NASA Glenn Research Center, local university astronomy departments, and local astronomical societies,” recalls Clyde Simpson, the Museum’s former Observatory Manager. “We were in the process of building the Reinberger Hall of Earth and Planetary Exploration, and pointed out we’d have good coverage of all lunar geology in that space. We asked for three different types of Moon rocks to put on display.”

The Museum had a detailed plan in place to incorporate information about these three types of lunar rocks into each of the small sections of Reinberger Hall, which had undergone renovations in 1997. The Museum was confident its extensive proposal would persuade NASA to be generous with its loans. Yet, obtaining three types of Moon rocks to place in the Museum proved to be quite a feat.

“[NASA] wrote back and said, ‘Who the heck do you think you are, the Smithsonian? Nobody gets three Moon rocks!’” Simpson says in jest. “‘But,’ they said, ‘your proposal was good enough. We’ll give you a nice big one.’”

The offer was certainly generous, but it didn’t come without strings. NASA requires the Museum to undergo an annual audit, in which the integrity of the alarm systems must be confirmed. The Museum also provides documentation on the annual number of visitors, and photographic evidence that the Moon rock is still here. Once these conditions are met, NASA approves the Museum’s loan for another year.

Today, among the worldly gems and jewels in Wade Gallery, you’ll find the Moon rock resting in its own case, under the spotlight. Walking by, you’ll likely hear children inquiring about the value of the priceless specimen. Their excitement about this marvel of man is contagious.

“Astronomy is an interesting subject, but sharing their enthusiasm for it was just a treat,” says Simpson, reminiscing about his career at the Museum. “Everyone likes astronomy; it’s one of the easiest hooks for science. There are people [who] don’t like lizards, or yawn at the mention of rocks, but you talk about the stars and everyone just goes, ‘Ooooh.’”