By John Mangels

Science Communications Officer

Pachycephalosaurs are a type of dinosaur known for their distinctive, thick-boned skulls. Some scientists think the heavy skull dome may have provided protection during head-butting or predator defense, while others say it could have helped attract mates.

A new analysis of skull pieces from three dome-headed pachycephalosaurs discovered in Mongolia is helping researchers, including Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology

Michael Ryan, Ph.D., learn more about how the animals’ heads changed as they grew.

The fossils are also clarifying relationships between a couple of types of pachycephalosaurs. The new research is published in the journal

Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology.

This illustration shows the pieces (shaded in gray) of three pachycephalosaur skulls that the research team examined. Views of each piece are from the side and from above.

This illustration shows the pieces (shaded in gray) of three pachycephalosaur skulls that the research team examined. Views of each piece are from the side and from above.

Immature skulls can look strikingly different from their adult forms. Those variations can make it hard to tell whether a fossil fragment from an extinct animal such as a dinosaur represents a newly identified species, or is a juvenile version of an existing species previously known only from adult fossils.

That’s especially true when scientists lack the rest of the skeleton and only have skull pieces to work with, which is the case with pachycephalosaurs.

Paleontologists have been waging this new-versus-existing species, adult-versus-juvenile debate about a dinosaur skull piece found in Mongolia in 1974. Its discoverer classified the find as a new pachycephalosaur species named

Homalocephale calathocercos. Other scientists have since argued that the flat, wedge-shaped skull top is an adolescent from a known pachycephalosaur species called

Prenocephale prenes. They contend that the animal died before its skull developed the round-domed shape that is characteristic of adult pachycephalosaurs.

Here’s where the more recently discovered skull pieces analyzed by Dr. Ryan and his colleagues come in.

They were unearthed by Japanese, South Korean and Mongolian researchers between 1994 and 2008 in a desert region of Mongolia, in a rock layer that’s between 66 and 72 million years old.

Lots of other kinds of dinosaurs have been found in this rock formation, but only a few pachycephalosaurs. That indicates either that pachycephalosaurs were rare in this part of the world (they’re common in North America, which was connected to Asia by a land bridge at the time), or that something about pachycephalosaurs — maybe their relatively small bodies — makes them less likely to be preserved as fossils. The animals were plant-eaters that walked on their hind legs, were probably no more than 10 feet long and weighed less than 1,000 pounds.

Dr. Ryan and an international team of scientists led by paleontologist

David Evans, Ph.D., of Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum, analyzed the three newer pachycephalosaur specimens — domes from the tops of two dinosaurs’ heads and a piece called a squamosal from the left rear of another dinosaur’s skull.

“Although I did not find any of the specimens while our team was in the Gobi Desert, I was one of the first to look at them closely,” Dr. Ryan says. “I realized that they might be able to help us sort out the problem of

Homalocephale, and I knew that I wanted my colleague, David Evans, a pachycephalosaur specialist, to look at them.”

The researchers used a CT scanner to see the interiors of the fossilized bones. They created 3-D computer models of the pieces, allowing them to be examined from any angle. They also shaved thin slices from the squamosal and one of the domes, giving them a close-up view of the microscopic latticework of fibers and cavities inside that make up the bones’ structure.

All three of the fossils appear to belong to the pachycephalosaur genus

Prenocephale, based on similarities to known specimens.

The scientists determined that one of the skull specimens — the smaller of the two domes —is likely from a non-adult

Prenocephale dinosaur. The microscopic cross-section showed telltale signs of fast-growing bone typical of an adolescent.

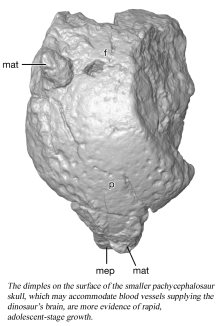

Also, the dome’s surface was dotted with small dimples that may provide room for blood vessels required by a growing brain. Judging by the appearance of other pachycephalosaur skulls, the dimples shrink in size and number and eventually disappear as a dinosaur reaches adulthood. Their presence in the Mongolian skull dome is another indication to the researchers that it belonged to an immature dinosaur.

The other two Mongolian specimens are likely from adults of various ages, considering their size and the lack of fast-growing bone structures.

Collectively, the three pachycephalosaur

Prenocephale skull pieces, along with others that Dr. Ryan and his colleagues reviewed, represent dinosaurs of a range of ages, from immature to adult.

The fact that the domed

Prenocephale skulls all look similar throughout the growth process — and that they look different than the flat, wedge-shaped

Homalocephale skull piece — strengthens the case that

Homalocephale is a different species of pachycephalosaur and not a juvenile

Prenocephale.

“Differentiating small adults of one fossil species from the juveniles of another closely related species will always be difficult,” Dr. Ryan says, “but this research goes a long way to sorting out the number of valid pachycephalosaur species in the Late Cretaceous of Asia.”