Fascinating facts about the ancient shark species Cladoselache

Hidden deep in the Museum’s underbelly is a large collection of Late Devonian fossil specimens that were found right here in Northeast Ohio. As far back as 1870, amateur collectors regularly stumbled across fossil evidence of strange aquatic life as they walked the southern shores of Lake Erie. As interest in these ancient specimens increased in the 1920s, dedicated excavation efforts began.

Using new Industrial Revolution–era technology, the steam-powered shovel allowed researchers to find fossils at a previously unimaginable rate. But one of the most prolific finds of these Late Devonian creatures came out of the 1966 Interstate 71 excavation project.

Led by former Cleveland Museum of Natural History Director William Scheele, a team of Museum researchers worked in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Transportation to carefully unearth the 358-million-year-old fossil-bearing shale concretions. The Late Devonian fossils they found nearly doubled the Museum’s collection—a collection so big, we’re

still studying it today!

Fossil hunters searching Cleveland shale during I-71 dig in October 1965

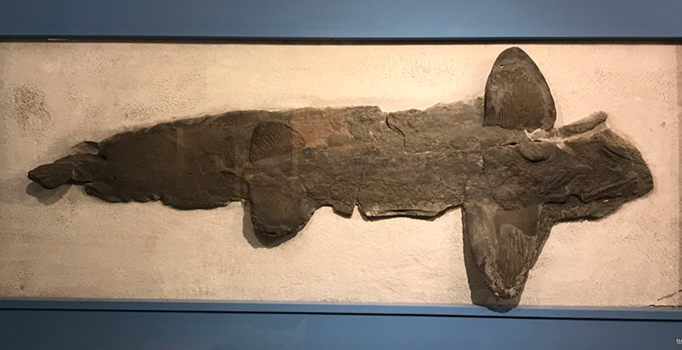

Cladoselache fossil found in the I-71 dig

Vertebrate paleontologists Amanda McGee and Lee Hall looking through the jaw of Late Devonian apex predator Dunkleosteus

You may be familiar with one of the most famous fossils of the Late Devonian Period—the Museum’s own Dunkleosteus terrelli, a giant, armored Devonian predator on display in the Kirtland Hall of Prehistoric Life. But today we’re taking Dunk out of the limelight to introduce you to another fascinating Late Devonian predator.

The species in question? Cladoselache.

The name Cladoselache comes from the ancient Greek and Latin roots clado, meaning “branch,” and selache, meaning “shark.” This name was inspired by the species’ unique branch-structured teeth, each one featuring five needle-like cusps.

Today you can visit the Museum to see a limited-time-only interactive exhibit, called Sharks in the Shale, which features some of the most complete examples of any ancient shark species in scientific history. These specimens are so well preserved that you can even see evidence of the “last meals” of some of these sharks. In fact, this partially digested, fossilized food is among the best-preserved examples we have on record of these types of prey fish as well.

The positions of the preserved stomach contents are important because they show us that Cladoselache may have skipped chewing its food with those formidable branched teeth altogether. Instead, the predator likely swallowed its prey whole, tail first. This leads researchers to believe that the fish was incredibly fast and agile—traits that would help as it attempted to out-swim the hungry Dunkleosteus.

Cladoselache specimen on permanent display in Kirtland Hall

In the exhibit, you can see the shark’s distinctive rows of teeth situated in the skull—teeth that would be replaced as they wore down (similar in concept to humans’ transition from baby teeth to adult teeth). The process was likely slower in this ancient species than it is in modern shark species. A particularly uncommon find in the specimens on display is the sclerotic ring around each eye socket, which helped the eye maintain its shape in the depths of the sea. Additionally, you can view the intermandibularis, or inside of the lower jaw, which elevated the floor of the mouth when swallowing; and the gill slits located near the neck area, which helped to filter oxygen. You may even notice evidence of the shark’s cartilage and soft tissue, features rarely preserved in fossils of this age.

The three-dimensional preservation of cartilage and soft tissues shows us that Cladoselache’s torpedo-shaped body, paired fins, rows of teeth, and gill slits looked similar to those of modern-day species of shark (like members of the order Lamniformes, such as the great white shark). However, there are key differences that set Cladoselache apart from the rest.

Perhaps the most visible difference is its terminal mouth, which makes these sharks look puppet-like, as opposed to modern sharks, which have longer snouts and offset mouths. Another easily observable difference is the shark’s distinct lack of placoid scales. The species does have some scales near the edges of the fins, mouth, and eyes, though most modern-day sharks have much more widespread scales that act as protection and aid in swimming.

The final, and perhaps most puzzling, difference is the species’ lack of reproductive claspers, a feature that is common in most sharks, both ancient and modern. Researchers have yet to identify how Cladoselache reproduced, leaving the door open for even more discoveries about this ancient species.

Another possible avenue of research is to determine why Cladoselache was so well preserved compared to other Late Devonian fish. While there is currently no peer-reviewed research on the topic, some hypotheses attempt to answer the question.

One theory is that the shallow, anoxic seafloor was unfriendly to the predators, scavengers, and even bacteria that would typically devour the carcass before it had a chance to begin the fossilization process.

There has also been speculation that the hydrogen sulfide content in the deepest parts of the sea may have played a role. Others believe that the shark’s urea-rich blood may have essentially “pickled” the body, allowing for quick preservation on the sludgy seafloor.

While no research has aimed to identify the exact reason for the essential “mummification” of Cladoselache, one thing is for sure—whatever facilitated this process has left modern-day researchers with remarkable fossils they can use to learn more about the fascinating primitive shark.

Be sure to visit the Museum to check out the limited-engagement Sharks in the Shale before this exhibit swims away!